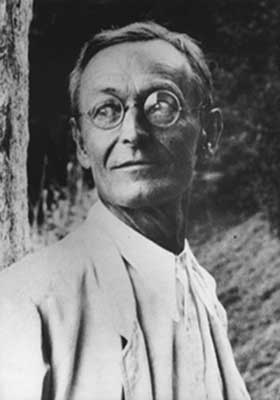

Hermann Hesse (1877 - 1962, Germany)

The possessor of perhaps the most refined and beautiful literary style. Reading Hesse for me is like drinking exquisite old wine, or listening to a favorite band through quality headphones, or skiing down a delightful powder slope during a snowfall. One could say that this man's books fully demonstrate the power and beauty of the German language. As far as I know, a prize in his name was even established, awarded for the most beautiful narrative and style in books.

The possessor of perhaps the most refined and beautiful literary style. Reading Hesse for me is like drinking exquisite old wine, or listening to a favorite band through quality headphones, or skiing down a delightful powder slope during a snowfall. One could say that this man's books fully demonstrate the power and beauty of the German language. As far as I know, a prize in his name was even established, awarded for the most beautiful narrative and style in books.

Regardless, Hermann Hesse was an artist, a poet, an extremely open person (which is already wonderful and rare), a humanist and pacifist who openly opposed both world wars. He saw human vices, social problems, the deep wrongness of the direction in which humanity is moving, yet was more than receptive to the beauty of the world, to the harmony of nature and the universe. As often happens, at the intersection of these two opposing feelings his work was born. This was nourished by the wisdom of the East: his grandfather lived in India for a long time, his mother was born there. Hermann was raised on a symbiosis of Christianity, Buddhism, and Taoism.

Steppenwolf (1927): a book about the wanderings and searchings of a sensitive but closed loner who cannot find his place in this new world of the 1920s. Throughout the book, the main character receives help, opens up, and understands what's what. I strongly recommend starting your acquaintance with Hesse through this work.

Siddhartha (1922): the story of Buddha. Essentially, a free retelling of Buddha's biography (whose name was Siddhartha Gautama) - stylized as a short novella, a description of the life path of "the one who awakened." As always, beautifully and, at the same time, filled with the deepest meaning. How could it be otherwise, since it's about the life of Buddha :)

The Glass Bead Game (1943): the key and final work of the author, which he worked on for 20 years. A masterpiece as it is. If you like Hermann's previous books, read this one.

The Glass Bead Game (1943)

CONCESSION

For those to whom all is clear from eternity,

Our bewilderments are idle fantasy.

Two-dimensional is the world, they answer back,

And to think otherwise is unsafe.For if we admit for a moment

That behind the surface yawn abysses,

Could we then trust comfort,

And would shelters be useful to us?

And therefore, to cut off frictions,

Let's renounce superfluous dimensions!

If the mentors judged honestly,

And all that awaits us is known in advance,

Then the third dimension is inappropriate.

Only he who is eternally ready to set off on a journey

Wins vigor and freedom.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 - 1832, Germany) - Faust

An exemplar of the amazing vivacity and depth of the German language, the culmination of German poetry. A book about the eternal dissatisfaction of human genius, about the wanderings and doubts of the soul, about the tormenting dualism within us. The main character is the semi-legendary figure of 15th-century European history, the scholar Faust, weary of life. His soul is staked in a wager between the Lord and the demon Mephistopheles; the latter must lead Faust into sin and thereby take his soul. Throughout the book, the scholar, together with the demon, explores the real world from which he had been separated by walls of books all his life, and also himself: Goethe through Faust undertakes a kind of journey into the wild and ancient unconscious. In the words of Carl Jung, "Faust dared to descend into the dark chaos of the historical psyche and immersed himself in the ever-changing unsightly side of life that rose from this boiling cauldron."

An exemplar of the amazing vivacity and depth of the German language, the culmination of German poetry. A book about the eternal dissatisfaction of human genius, about the wanderings and doubts of the soul, about the tormenting dualism within us. The main character is the semi-legendary figure of 15th-century European history, the scholar Faust, weary of life. His soul is staked in a wager between the Lord and the demon Mephistopheles; the latter must lead Faust into sin and thereby take his soul. Throughout the book, the scholar, together with the demon, explores the real world from which he had been separated by walls of books all his life, and also himself: Goethe through Faust undertakes a kind of journey into the wild and ancient unconscious. In the words of Carl Jung, "Faust dared to descend into the dark chaos of the historical psyche and immersed himself in the ever-changing unsightly side of life that rose from this boiling cauldron."

This is an emotionally powerful and meaning-packed work, saturated with ideas, alchemy and symbolism, steeped in European mysticism. I myself plan to reread Faust in the future: both for pleasure and because of a feeling that I will extract much more from this source.

Faust (1832)

So, pedant, you need a check,

And a man doesn't inspire your faith?

But if oaths mean nothing to you,

How can you think that a scrap of paper,

A worthless piece of obligation,

Will hold back life's raging current?

On the contrary, amid this torrent

Only the sense of duty remains sacred.

The awareness that we owe,

Pushes us to sacrifice and expense.

What is the power of ink compared to this?

It amuses me that word has no credit,

While the naked ghost of writing

Has enslaved everyone with the tyranny of the letter.

Victor Hugo (1802 - 1885, France)

Hugo cuts to the depths of the soul.

Hugo cuts to the depths of the soul.

First - it's masterful style and deepest attention to detail: thus, reading and understanding him, you teach yourself to formulate thoughts just as clearly, fully, and beautifully. He seems to deliberately bring every sentence to its final, most saturated form, thereby challenging notions of how fully one can use language. Since this is prose, Hugo's books lack the necessary abbreviations and modifications for rhyme, but this doesn't deprive his language of poetry.

Second, Victor leads the narrative as slowly as possible: for each character, their background is given, the peculiarities of their character and their personal story, and for each event, extensive cultural and historical context is provided. Because of this, reading, for example, Les Misérables (1862), I became more closely acquainted with French culture, with their way of thinking, but also with their history - quite thoroughly. Hugo describes the years before the revolution, the revolution itself, and its consequences so meticulously and vividly that it far surpasses any history textbooks. At the same time, the style and picturesqueness allow you to almost feel the cobblestones of Parisian streets and the smell of gunpowder on the barricades, or feel the clumps of earth flying in your face from nearby artillery volleys of the English army at the Battle of Waterloo.

Third, Hugo synthesizes style and historicity of writing in a plot (I mean Les Misérables) whose emotionality and intricacy easily surpasses War and Peace. It's a colorful, soul-gripping story that doesn't let go until the very end and more than once causes exclamations of joy or tears. Perhaps I have read nothing so sad and emotionally powerful.

Besides Les Misérables, I recommend "The Man Who Laughs" (1869). It's much shorter and about England, but the level is absolutely the same.

Les Misérables (1862)

To see a thousand things for the first and last time — what could be sadder and at the same time more profound!

To travel is to be born and die every second.

Such a man would doubtless be worthy of having no political convictions. Let our thought not be misunderstood — we do not confuse so-called "political convictions" with the lofty aspiration for progress, with the sublime faith in country, in people, and in man, which in our days should be the foundation of the worldview of every noble thinking being.